Scripting Gaia Sky

Random thoughts on the Gaia Sky scripting system

Scripting Gaia Sky with Py4J

Gaia Sky has a quite powerful Python scripting system which has gotten a revamp lately. The system exposes an API which can be used from Python scripts to interact with an instance of Gaia Sky running in the same machine (so far). But to understand where we are, we need to know where do we come from.

Where do we come from?

Up to Gaia Sky version 2.1.7, we used Jython to run the scripts. Jython is a Java implementation of Python. With it, it is possible to run a Python interpreter inside the JVM and have virtually unlimited access to the JVM objects and features. This allowed for a seamless integration between Gaia Sky and the scripts. You could have very easy access to everything from a script. This, of course, introduced lots of risks. For one, it was very easy to create a script which completely destroyed the Gaia Sky instance:

The ‘official’ way of interacting with Gaia Sky was an object called EventScriptingInterface, which is an implementation of the API at IScriptingInterface:

| |

However, nobody was prevented to create and run something like this script, let’s call it gaiasky-killer.py.

| |

This very short script would kill the running instance of Gaia Sky in the blink of an eye. It is not a very severe vulnerability, as the user needs to explicitly run the script to make it happen, and at the end of the day only Gaia Sky is killed, which itself runs in a sandboxed JVM. But still.

Other drawbacks derived from using Jython are listed here:

- No new versions since 2015 - dead project?

- Only Python 2.7 supported

- Tiny wee bit of Python - no additional modules, no native code (forget about

numpy) - Very sizeable dependency (~40 MB, about 1/3 of Gaia Sky’s package size)

After examining and weightin these issues, we decided to do away with Jython and use Py4J instead. So, where are we going?

Where are we going?

The new system uses Py4J, a layer which, in their own words, “enables Python programs running in a Python interpreter to dynamically access Java objects in a Java Virtual Machine”. What does that mean for Gaia Sky? Basically, as of version 2.1.8, the scripts are not ran from within Gaia Sky anymore. The car icon button at the bottom of the controls window to parse and run scripts is not be there anymore. Instead, the user must run the scripts herself using whatever Python interpreter he chooses. The scripts connect to a locally running Gaia Sky instance via Py4J.

This opens a world of possibilities. For starters, Python 3 may be used. Also, Gaia Sky scripts can use any other Python libraries existing in the installation, such as numpy or scipy. Also, access to the JVM is very restricted, and achieved via proxy objects and direct translations. This adds an extra layer of security. We only expose the EventScriptingInterface, this time for real.

The new scripts will need to import and create the py4j Java gateway, and then use its entry_point to acces the API. At the end of the script, it is necessary to close the gateway object.

| |

The initialisation with auto_convert=True enables the automatic conversion from Python collections to their java counterparts. This is not strictly necessary, but highly recommended. Otherwise, you need to do the conversion yourself before sending the objects to the Java side via the API calls. In our case, we only ever send double[] array objects, so we duplicated the methods which need such parameter types so that they accept instances of java.util.List as well. This makes them work with the automatic conversion provided by Py4J, and it is very convenient for the user, since now she can pass Python lists directly to the API.

How to run scripts

We mentioned that before we ran the scripts with Gaia Sky itself. This is no longer true. Now, the user needs to run the scripts using her Python interpreter. Bring up a terminal window and run your script like this:

$ python my-gaiasky-script.py

It is even possible to open a Python interpreter and interact with Gaia Sky in real time, or even debug the scripts with pudb!

The following video showcases an interactive session where a Gaia Sky instance is manipulated in real time from a Python interpreter (Youtube link).

Parameter types

Another point to mention is that Py4J is very strict with the parameter types. Before, we could use integer values as floating-point parameters and the Jython-Java tandem would do the conversion automatically, just as if the calling code was in Java. Now, we can’t pass an integer to a location where the API expects a float. We try to mitigate this by creating several method definitions accepting all combinations of double and long, but still it is generally safer to stick to the types defined in the API.

For example, the API method

double[] galacticToInternalCartesian(double l, double b, double r);

must not be called like this:

gs.galacticToInternalCartesian(10, 43.5, 2)

Call it like this instead to avoid problems:

gs.galacticToInternalCartesian(10.0, 43.5, 2.0)

Callbacks

Before, it was very easy to implement Java interfaces from Python to implement functionality from scripts. For instance, some API calls get a runnable object and park it after the main loop, so that the code in run() is executed once every cycle of the main loop.

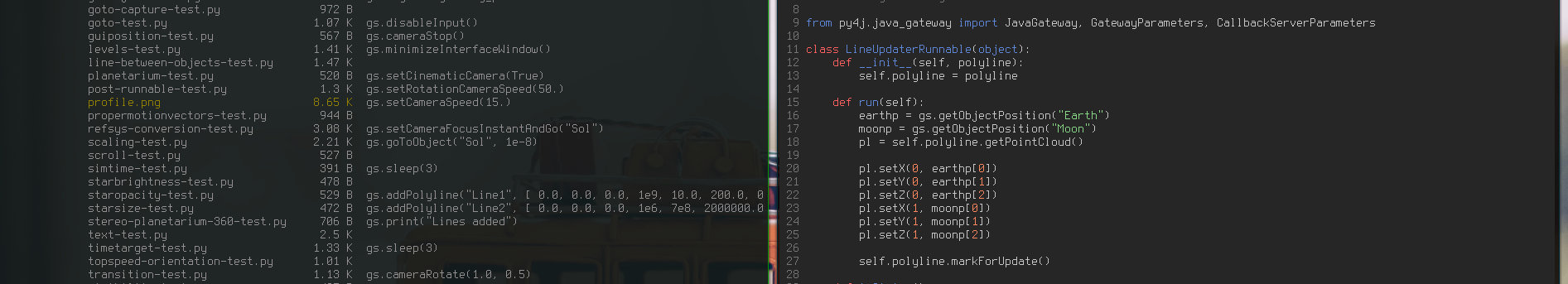

The new system also allows for this kind of behaviour. Now, we need to add an extra object CallbackServerParameter to the recipe, enabling the synchronization of the shared objects. Let’s see an example:

| |

This example parks a runnable that counts frames for 15 seconds. A more useful example can be found here. In this one, a polyline is created between the Earth and the Moon. Then, a parked runnable is used to update the line points with the new postions of the bodies. Finally, time is started so that the bodies start moving and the line positions are updated correctly and in synch with the main thread.

More examples

You can find more examples in the scripts folder in the repository.

Conclusion

I think the Gaia Sky scripting system is in a better state after the move from Jython to Py4J. We have lost little functionality and we have gained a lot of flexibility. The responsibility to run scripts is now on the user’s shoulders, and we have a more secure and robust system as a result.